THE PREDICTABLE RISE OF AD-BLOCKING

- Mar 22, 2017

- 6 min read

My teenager walks over to my computer and mocks me: “Why are you not blocking all of these ads?”.

I sigh. I look at him and explain, “These ads are putting food on the table.”

That confirms my age anyway. It also let’s you know where I fall on the topic of ad-blocking technology. And when and where did my own offspring become an ad-blocking advocate?

Given my experience in the industry I have a theory. In retrospect, this ad-blocking trend was predictable and inevitable based on decisions and priorities made by advertisers, agencies and publishers years ago.

When the digital advertising industry became acutely aware of a problem with 'viewable ad impressions', this resulted in a chain of reactions and responses that resulted in a web-browsing experience that has accelerated ad-blocking from 21 million users in 2010 to more than 144 million today (see Pagefair https://pagefair.com/intel/ )

So here’s what happened.

THE PROBLEM: DISCREPANCIES IN THE NUMBERS

Some well-meaning people were aware that publishers would charge for every ad impression delivered by their ad server; And many advertisers were painfully aware of a discrepancy between what the ad impressions a publisher claimed to have delivered, compared to lower numbers reported by their own ad-server.

There are many reasons for this discrepancy, but that isn't the point of this post. The point is that there was no way to audit or quantify the numbers to determine whose were accurate - or no easy and repeatable way to do this. This was a 'problem' in search of a solution.

THE SOLUTION: TECHNOLOGY WILL REVEAL THE TRUTH

The ongoing issues and ambiguity with ad counting created a certain amount of skepticism with ad delivery for advertisers.

So the “ad verification” industry was born.

To address many issues around ad delivery, and to fill the gap in the industry for some sort of independent accreditation authority (such as the Audit Bureau Circulation for print or Nielsen for TV), a new set of technology tools and platforms was presented to the advertising and publisher community.

I recall many of my early meetings with some of these solution providers. They pitched their technology to advertisers and agencies with the compelling argument that “Do you REALLY know how many people actually see your ads?”

Of course, agencies and digital media buyers are competitive folks, and live in mortal fear that one of their competitors will point out some major flaw with the whole digital advertising ecosystem, which will make them look bad if they weren’t already on top of the issue.

Slowly at first, advertisers and agencies started using these new ‘verification services’ – and what they discovered terrified them.

They discovered that the average ‘viewability’ was often below 50% of the impressions on some web publishers.

Clearly, this is bad news. This means that half (or more) of the ads you paid for were not seen by a real person.

Some of this inefficiency was actually built into the system (and, as I'll point out below, the pricing even indirectly reflected this). Many web publishers would often sell ad placements 'below the fold' at a steep discount compared to 'above the fold' placements. However, this was not always possible as many placements with ad networks couldn't be easily segmented.

In case you're unclear on what it means to be 'viewable' or 'above the fold', here's a simple image which shows you what that means. A browser window only shows a portion of the total content on a web site. The viewer must scroll down the page to see more. If they don't then they will not see any of the content outside of the browser window (shown below in light grey).

THE INDUSTRY REACTION: "THE GREAT VIEW-ABILITY FREAK-OUT"

And thus began the great “Viewability Freak-Out". All of sudden fingers were being pointed at the "unscrupulous" web publishers who had been "ripping off" advertisers for years, by selling them ads that were never seen! I'm being overly dramatic, but there was an underlying assumption that even credible publishers who had low viewability were somehow up to no good.

THE PUBLISHER RESPONSE: MAKE ADS MORE VIEWABLE

The reaction from publishers (who need to sell ads to produce all this free content) examined different ways to address their viewability problem:

“How do we make ads more viewable?”

I think this is when things went bad for users. The truth is that people don’t WANT to see ads, but they will tolerate them up to a point.

So many publishers started creating new ad experiences that made it hard for users to ignore ads: Ads that follow you as you scroll, ‘native’ ads that break into content you are reading, mandatory ad exposures before you can see content, and on and on.

THE USER RESPONSE: I'M SICK OF THESE ANNOYING ADS!

When you irritate people to the point where they now feel motivated to solve a problem, you've crossed a line. My theory is that many of these new ad experiences created that line for many people.

As a result, ad-blockers started to seem like a more logical way to address this problem for many users. Of course there are a number of other reasons but I believe that a perceived increase in the 'viewability tax' for users may have been a significant factor in this.

The below chart – based on Google searches – demonstrates the rise in interest for ad blockers from frustrated users since 2010:

Yes, 'view-ability' increased - but at the expense of user experience. Ads forced into your web-browsing experience is not what people were used to nor what they wanted. Sadly, the industry should have recognized the counterproductive results of forced ad experiences.

RESULT: A LOSE-LOSE FOR PUBLISHERS AND USERS

Advertiser and publishers should have been able to predict that if they make ads more ‘annoying’ to the users, users will find ways to avoid it. DVR’s could have been considered an example of how users will react to ads when a certain tolerance threshold is exceeded. They should have looked at the issue from an economic, and not a moral perspective. The question should NOT have been ‘why am I paying for all these ads that no one ever sees?’ but rather, ‘How much do I pay for the ones that are being seen?” or "How much am I paying for the people that take action after seeing/clicking on my ads?" It's evident that users AND publishers lose as a result of the 1) aggress ad experience and 2) reduced ad revenue (respectively). What about the advertisers? Have they gained? Aren't their campaigns better with this improved view-ability? If higher view-ability scores matter, then yes, the advertiser may have gained. In terms of actual return on ad spend? Probably not.

RESULT 2: THE LAW OF SUPPLY AND DEMAND MEANS NO IMPROVEMENT FOR ADVERTISERS RETURN ON AD SPEND.

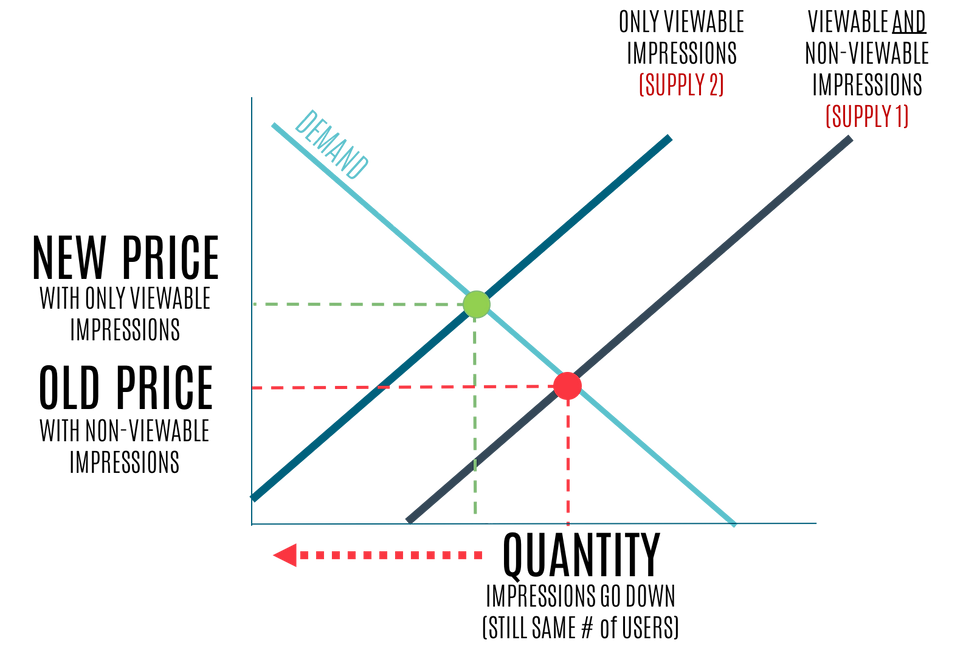

Most decent digital publishers use some form of yield management system which is based on supply and demand. When this is the case and 'supply' (the impressions) go down but demand stays the same the price will increase. This is what the supply and demand curves look like.

Now, advertising is a bit strange. Because it's commonly purchased on an 'impression' basis and not a 'user' (or viewer) basis, so someone could legitimately say that there was no 'price increase, and they may be correct. But all things being equal in this scenario, the cost for an actual view likely was the same as it was prior to the changes, or may have increased. Keeping in mind that the impressions declined but the users stayed the same (and so did demand), the cost per viewed impression likely was unchanged:

This is just my hypothesis. It could be wrong. But I think it's a good example of the law of unintended consequences.

When the industry got serious about solving the viewability program, it should have really examined the impact on users and how they might respond. To my knowledge, this wasn't a priority.

I never bought into ‘viewability’ as a great metric. Yes, accuracy is important. Ambiguity and discrepancies should be removed as much as possible. But what really matters is the return on investment and how people respond based on the cost of that ad.

After all, what’s the ‘viewability’ of a TV ad? Or a radio ad? Setting aside DVRs, are you really ‘paying attention’ to all ads in the commercial block? Or are your looking at your phone?

And yet TV ads are still evaluated on their results, not their viewability.

Maybe we need to be more creative in digital ads, and less focused on viewability?

DOES IT MATTER ANYMORE?

The growth of ad-blocking software certainly hurts publishers in the form of lost revenue, as 'free-loading' ad-blocking users avoid the primary means of income for publishers to create quality content. And certainly, Facebook is changing the entire model for many publishers, so perhaps much of this is irrelevant. If these trends continue it could mean more subscription based models for digital content, or even more annoying ads to force users to see ads. Even the New York Times notices!

Of course, this is just my opinion. For me, the moral of the story is to deeply consider the long term consequences of our immediate reactions to perceived problems.

For the world's children the loss is much deeper as they will never experience the joy of clicking on a banner.

Comments